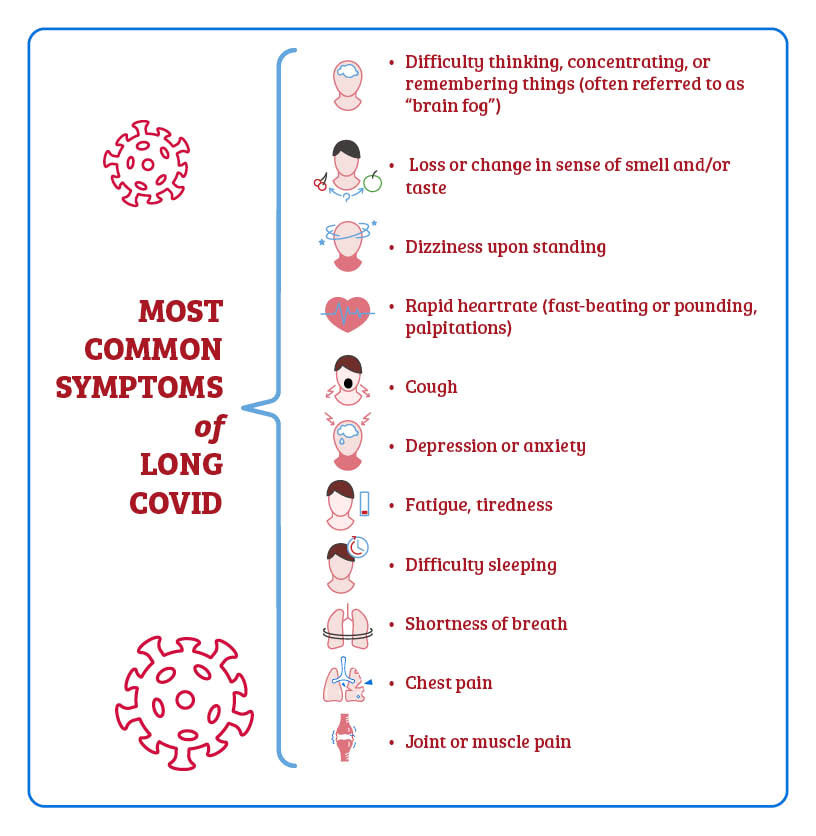

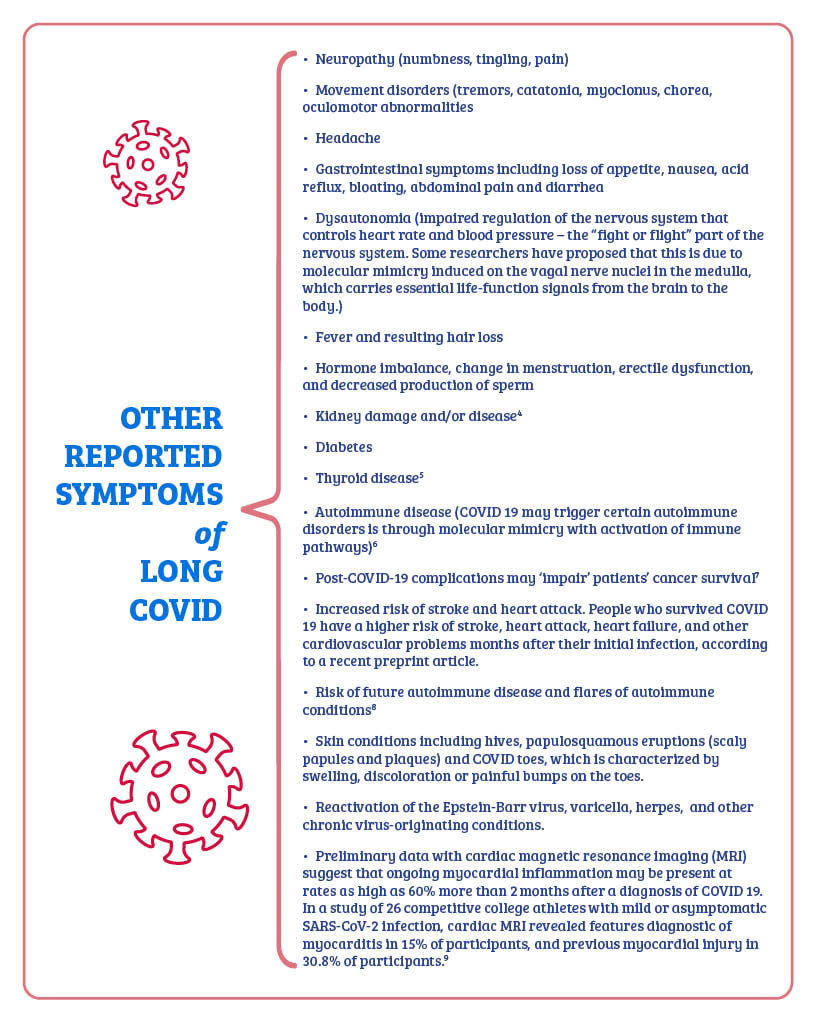

Detailed in our first article[FG1] , long COVID (also known as long-hauler COVID, post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS), and LTC-19) refers to the chronic disorder marked by the presence of multiple, diverse symptoms for more than 90 days after a COVID infection. Clinicians are seeing long COVID occur even in cases where an infection was mild, making it more perplexing to assess and treat those affected patients. (maybe put this in a color just to break up regular text a bit?) Just a few of the symptoms…and possible health risks. Neurological & cognitive issues Sleep difficulties Neuropathic pain Respiratory problems Increased risk of stroke A more extensive list is shown below... What do the studies tell us? Scientists and physicians are identifying the effects of long COVID in real time – so the data is continually being updated as new information comes to light. But it’s clear that many patients are reporting a wide range of lingering problems, including neurological symptoms. For example, at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, researchers working with long-hauler patients in their PACS facilities conducted a survey of over 150 patients from 82 to 457 days following a COVID infection. Of this group, fatigue was cited by 82%, brain fog by 67%, with headaches occurring in 60%. As expected, any physical exertions worsened symptoms in 86% of the respondents; stress and dehydration also tended to exacerbate the issues. As far as additional neurological impacts, 63% reported signs of mild cognitive impairment and those surveyed also cited anxiety and depression among their ongoing effects.1 Other reviews that collected clinical and para-clinical data from also found that up to 84% of COVID 19 patients experienced neurological impacts like brain fog as loss of taste or smell (anosmia), epileptic seizures, cognitive impairments, loss of consciousness, confusion, and incidence of strokes.2 Researchers noted that there was a high incidence of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, a brief but intense inflammation (swelling) in the brain and spinal cord; note that in some cases, the use of intravenous immunoglobulin was instrumental in achieving improvement for this particular effect. An October 2021 publication in JAMA Network Open reported on a data analysis of a cohort study of 740 patients at Mount Sinai Health System during the period of April 2020 to May 2021. Scientists noted “a relatively high frequency of cognitive impairment several months after patients contracted COVID-19.” Impairments in executive functioning, processing speed, category fluency, memory encoding, and recall were predominant among hospitalized patients. And while impairments might have been expected to occur more frequently in older populations, the study showed that younger demographics were also affected, further supporting the need to identify effective long-term treatment and rehabilitation protocols for all patients.3 The additional impacts. Scientists are also investigating the effects of long COVID in a unique subset of patients – athletes, specifically soccer players. A study conducted in Germany and Italy found that performance among players after a COVID infection evidenced measurable dips and was still below their original performance stats at least six months after the infection. So, while there is usually a rapid recovery from an illness like the flu, for example, this has not been the case with the coronavirus. In their discussion paper, “The Long Shadow of an Infection: COVID-19 and Performance at Work,” authors detail the grave concern and implications regarding not just the professional sports industry, but also the issues faced by workers in other fields – and subsequent effects on world economies and already-burdened healthcare systems. And another very concerning study coming out of the U.K. looked at magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) from a biobank of over 40,000 and invited 785 post COVID patients back for repeat imaging. Researchers compared the two scans and then added 384 control subjects who had either tested negative to rapid antibody testing or had no history of being infected with COVID-19. The findings were quite alarming – there was an obvious reduction in gray matter post-COVID, with a marked reduction of gray matter thickness in fronto-parietal and temporal regions, both of which are responsible for executive functions such as memory and language-based decoding. And, perhaps just as concerning, there was no significant difference among patients who had been hospitalized and those who had mild cases of COVID. The WHO definition of long COVID and the symptoms. The World Health Organization (WHO) and panel comprised of clinicians, researchers, patient groups and policy-makers, representing different nations, released its formal definition of long COVID (or post-COVID 19 condition), stating it “occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset of COVID-19 with symptoms and that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis.” Additionally, the panel noted that “common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive dysfunction but also others and generally have an impact on everyday functioning. Symptoms may be new onset following initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or persist from the initial illness. Symptoms may also fluctuate or relapse over time.” To date, we know that symptoms of long COVID, some of which may worsen with physical exertion, can include but are not necessarily limited to: An estimated 25 to 35% or more of all diagnosed COVID patients are experiencing at least some of these long-hauler symptoms in varying degrees of severity. It is crucial that physicians and scientists continue to study this complex landscape in order to expediently identify the most appropriate therapies in order to improve the outcomes for all patients.

In hope and healing, Dr. Suzanne Gazda Next up in our series…Why does long COVID occur? References: 1 Tabacof L, Tosto-Mancuso J, Wood J, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome negatively impacts physical function, cognitive function, health-related quality of life and participation [published online ahead of print, 2021 Oct 20]. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;10.1097/PHM.0000000000001910. doi:10.1097/PHM.0000000000001910 2 Ross W Paterson, Rachel L Brown, Laura Benjamin, et al. UCL Queen Square National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery COVID-19 Study Group. The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology: clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain, Volume 143, Issue 10, October 2020, Pages 3104–3120, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa240 3 Becker JH, Lin JJ, Doernberg M, et al. Assessment of Cognitive Function in Patients After COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2130645. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30645 4 https://medicine.wustl.edu/news/covid-19-long-haulers-at-risk-of-developing-kidney-damage-disease/ 5 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214624521000174 6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7499017/ 7 https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/959251 8 Winchester N, Calabrese C, Calabrese LH. The intersection of COVID-19 and autoimmunity: What is our current understanding? Pathog Immun. 2021;6(1):31-54. doi:10.20411/pai.v6i1.417 https://www.paijournal.com/index.php/paijournal/article/view/417 9 Julian A. Luetkens, Alexander Isaak, Can Öztürk, Narine Mesropyan et al. Cardiac MRI in Suspected Acute COVID-19 Myocarditis. RSNA. Published Online:Mar 4 2021 https://doi.org/10.1148/ryct.2021200628.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSuzanne Gazda M.D. Neurologist Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed